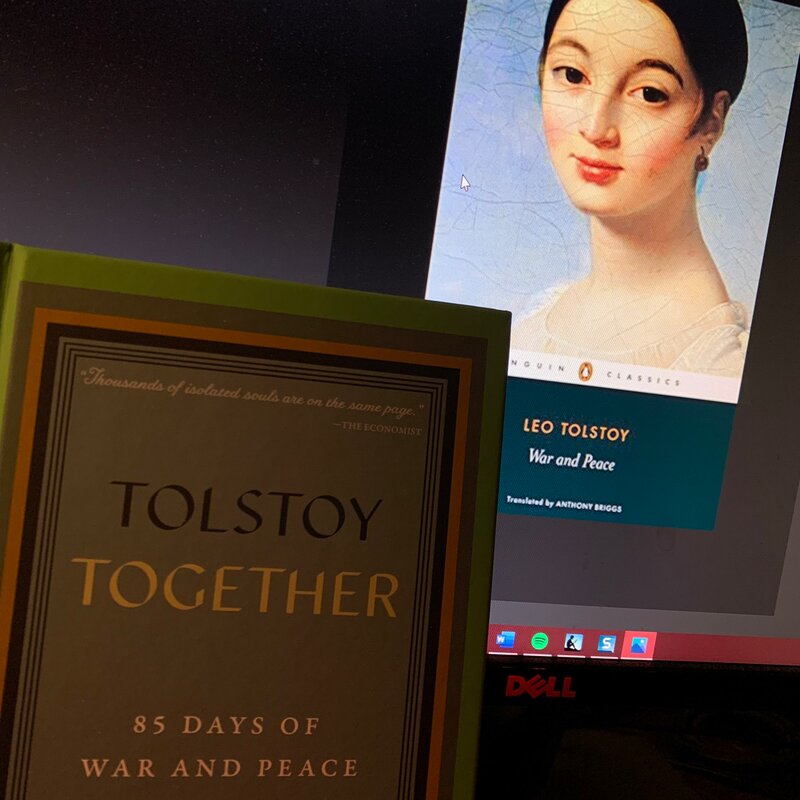

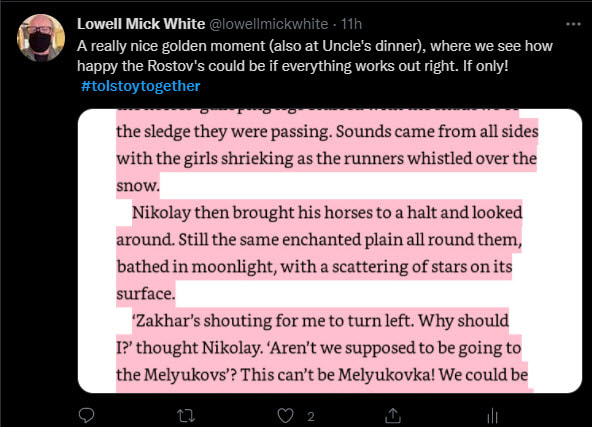

This is the second time through. TT began during the first covid lockdown and was terrific, and resulted in a nice little volume of selected tweets. I have a minor contribution to the book and was/am delighted to be a part of it.

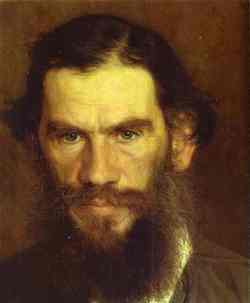

As a side benefit of Tolstoy Together, I am amassing a nice collection of War & Peace slides, which will be handy if I ever teach the book in a class--which I would love to do....

Everybody needs to read War & Peace. Everybody who reads W&P should get Tolstoy Together….

RSS Feed

RSS Feed